I went home and it happened.

I went home and it happened.Monday, December 28, 2009

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Friday, December 11, 2009

edible

My mom sent me an email last weekend requesting me to emotionally prepare myself to have my photo taken with my brothers by a proffessional photographer when I go home for Christmas. I started thinking about myself as me-the-sister with my getting-longish hair seated next to my brothers Will and Dennis... and then later that night I cut my hair off in my kitchen with a pair of craft scissors with Morgan and Emmet watching.

My mom sent me an email last weekend requesting me to emotionally prepare myself to have my photo taken with my brothers by a proffessional photographer when I go home for Christmas. I started thinking about myself as me-the-sister with my getting-longish hair seated next to my brothers Will and Dennis... and then later that night I cut my hair off in my kitchen with a pair of craft scissors with Morgan and Emmet watching.I'm not very good at getting my picture taken, whatever that means. I guess maybe that means that I don't do the right poses, whatever those are. I guess maybe those are the ones that make me look articulate, well-packaged and edible like a piece of biscotti. I think that a photo album comprised of photographs of me probably looks something like a spaghetti cookbook.

I'm excited about this project though and all of the questions and considerations going into it. Where should we be, what should we wear? It made me remember that a lot of these pictures I'm looking at seem accidental but are really incredibly composed. I love the kid in this picture-- she's totally a noodle dish like me.

the perfect photograph

We expect the perfect photograph to be both different from what it shows so that it may add to the phenomenal repository of the world, and wholly indifferent to its own condition so that it may act as a neutral intermediary between subjective vision and an objective view. The drive towards photographic perfection strives for pictures which are at once ever more life-like and ever more unlike anything else in life; images which create and recreate the world as it appears to our eyes, in colour and perpectival depth, but also as it is beyond the threshold of perception, in greater detail, at a greater speed, from a greater distance, in a word, enhanced. The desire for the perfect image, as transparent as it is evident, is a desire to see both more and less of photography.

We expect the perfect photograph to be both different from what it shows so that it may add to the phenomenal repository of the world, and wholly indifferent to its own condition so that it may act as a neutral intermediary between subjective vision and an objective view. The drive towards photographic perfection strives for pictures which are at once ever more life-like and ever more unlike anything else in life; images which create and recreate the world as it appears to our eyes, in colour and perpectival depth, but also as it is beyond the threshold of perception, in greater detail, at a greater speed, from a greater distance, in a word, enhanced. The desire for the perfect image, as transparent as it is evident, is a desire to see both more and less of photography.-Pavel Buchler in his book of essays on photography and film, Ghost Stories

Thursday, December 10, 2009

something jane said

Last weekend I was given this enormous tin-type by another CCA student in my studio building named Rebecca Wallace-- a frame repairman she knows found it taped on the back of an old mirror. It's about 8 inches tall and 6 inches wide-- once made with a huge camera with the weight and portobility of a mini-fridge. The images background is etched with acid to make it look brown, the face and dress of the woman painted and drawn upon to add to its coloring and detail. Some of this drawing is comically clumsy. I've never even seen a tin-type this large and can't stop thanking Rebecca for this amazing gift. And now for something era-appropriate, written by Jane Austen in her novel Mansfield Park.

Last weekend I was given this enormous tin-type by another CCA student in my studio building named Rebecca Wallace-- a frame repairman she knows found it taped on the back of an old mirror. It's about 8 inches tall and 6 inches wide-- once made with a huge camera with the weight and portobility of a mini-fridge. The images background is etched with acid to make it look brown, the face and dress of the woman painted and drawn upon to add to its coloring and detail. Some of this drawing is comically clumsy. I've never even seen a tin-type this large and can't stop thanking Rebecca for this amazing gift. And now for something era-appropriate, written by Jane Austen in her novel Mansfield Park."If any one faculty of our nature may be called more wonderful than the rest, I do think it is memory. There seems something more speakingly incomprehensible in the powers, the failures, the inequalities of memory, than in any other of our intelligences. The memory is sometimes so retentive, so serviceable, so obedient; at others, so bewildered and so weak; and at others again, so tyrannic, so beyond control! We are, to be sure, a miracle every way; but our powers of recollecting and of forgetting do seem peculiarly past finding out."

There were times.

There was a night when I was 6 years old that I was certain I would die in my sleep. We were at my grandparent’s home on Long Island, back when they lived in the tall pink Victorian house, a house which was definitely haunted. That night I was in what had once been my Uncle Mark’s room-- my parents were sleeping in a bedroom far away on the other side of the house. To get to their room I had to walk by a big hollow bathroom, through a foamy green colored bedroom with crocheted stuffed animals and white wicker furniture, past the drone of late-night television through the door of my grandparents room, down a long wooden floored hallway, around a corner and by the huge front staircase where the stained-glass windows seemed to undress you when you stood in front of them at night. Will had been born and was a year old which meant he got to sleep with my parents and I did not. My mother put me to bed and I cried in the dark, panicking that I might fall asleep. Eventually I turned the light on and looked at the comics in a big stack of Reader’s Digests in the closet. The carpet was shag and a strange combination of orange, lime green and mustard yellow.

There was a night when I was 6 years old that I was certain I would die in my sleep. We were at my grandparent’s home on Long Island, back when they lived in the tall pink Victorian house, a house which was definitely haunted. That night I was in what had once been my Uncle Mark’s room-- my parents were sleeping in a bedroom far away on the other side of the house. To get to their room I had to walk by a big hollow bathroom, through a foamy green colored bedroom with crocheted stuffed animals and white wicker furniture, past the drone of late-night television through the door of my grandparents room, down a long wooden floored hallway, around a corner and by the huge front staircase where the stained-glass windows seemed to undress you when you stood in front of them at night. Will had been born and was a year old which meant he got to sleep with my parents and I did not. My mother put me to bed and I cried in the dark, panicking that I might fall asleep. Eventually I turned the light on and looked at the comics in a big stack of Reader’s Digests in the closet. The carpet was shag and a strange combination of orange, lime green and mustard yellow.In his book, Many Lives, Many Masters, psychiatrist Brian L. Weiss writes, “How powerful the fear of death is. People go to such great lengths to avoid the fear: mid-life crises, affairs with younger people, cosmetic surgeries, exercise obsessions, accumulating material possessions, procreating o carry on a name, striving to be more and more youthful, and so on. We are frightfully concerned with our own deaths, sometimes so much so that we forget the real purpose of our lives (59).” I may have been a mere six years old, but that night alone in my uncle’s old bedroom in my grandparents house on Long Island, I was acutely aware of my own mortality. It was a strange experience to sleep in either of my grandparents’ homes when I was small and perhaps even still— I was existentially disturbed by the idea of my parents having once been children and having once slept in the same bed I was expected to.

There was a night when I was 10 years old that I found a copy of Anne Frank’s diary on the bookshelf in the old bedroom of another uncle at my grandparent’s home in Indianapolis. I read it in a single night with my brother Will sleeping in the bed next to mine. The fake candles flickered in the windows. Historical prints of soldiers and ships hung in couplets on the walls. A dark leather armchair slumped in between the closets and the ticking of a manually-wound alarm clock counted out the passing seconds. That night I experienced my second mortal revelation—whereas when I was six and in Long Island I realized that I might die, when I was ten and in the mid-west I realized that I definitely would. At some point in the night I realized Anne Frank was like me, followed by the realization that I could have been Anne Frank, and then by the time it was morning, that I was Anne Frank.

The main narrative of Weiss’ book chronicles his first experience with a patient who regresses to previous lives while under hypnosis. The patient, whom he calls Catherine, had been experiencing severe anxiety attacks, recurring nightmares and chronic depression. After months of unsuccessful therapy Weiss and Catherine decide to use hypnosis in their sessions in an attempt to reveal subconscious memories of traumatic events. Hypnosis is explained by Weiss as a useful therapeutic tool in which the therapist helps distract the patient from external stimuli and focus on memory retrieval. In their first session Catherine recalls a traumatic experience at the dentist at age 6, a memory of nearly drowning at age 5, and then one of being molested her father at age 3. Over the next week her symptoms fail to improve so they continue with hypnosis to see if other traumatic memories can be revealed. In her next session, to Weiss’s surprise, she regresses past her childhood to a previous lifetime, the first of many. In later sessions she speaks from these previous incarnations and the space between lives, having conversations with a cast of superior spirits whom Weiss refers to as “the masters” who say that she has lived 86 times before.

There was a time when I was young that my grandmother sat down with me on her plaid couch and showed me pictures of my father as a child and herself as a young woman and pointed out that I had her fingernails, but that I had my mother’s nose. My father as a baby in a black and white photograph had a lumpy head, which my grandmother told me was because he was pulled out of her birth canal with forceps. My father and uncle playing in front of an unrecognizable house. My father with other girlfriends who were not my mother. My father with long hair. My father with no facial hair. My third mortal revelation: my father was a stranger, perhaps many strangers. My grandmother also showed me pictures of a baby with blonde hair and asked me if I knew who it was. I recognized her implication and correctly guessed that they were myself—though the child in those photographs bore no resemblance to anyone I had ever met before.

Through Weiss’ mediation and resolution of traumatic events in her previous lives Catherine experiences relief from her contemporary symptoms, although she has no recollection of her hypnotized revelations. Weiss continually references his classical and scientific academic training and expresses his doubts and fears of ruining his career by going public with these revelations: “But were there other explanations for Catherine’s past-life memories? Could the memories be carried in her genes?... What about Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious, a reservoir of all human memory and experience that could somehow be tapped into? Divergent cultures often contain similar symbols, even in dreams. According to Jung, the collective unconscious was not personally acquired but “inherited” somehow in the brain structure… [but] Jung’s ideas seemed too vague… All in all, reincarnation made the most sense (105-106).”

There was a Sunday at the Unitarian Universalist church in Princeton, New Jersey that my father tried to entertain the waning interest of our 3rd-5th grade Sunday school class with a videotape about reincarnation. We sat on the putty-colored linoleum floor. There was snow outside. The week before we had learned about Egyptian mummification. As I recall, the majority of the video featured characters who waited in a white room with lots of doors and windows while they learned about their past lives and the ones they were about to be born into. The cast was multi-racial and comprised of a range of represented ages and personalities. I remember being vaguely interested but was distracted by the rarity and significance of the fact that we were watching television at church. This was a different kind of movie because it lacked the linearity that I was used to—it didn’t show a single story told from start to finish, the seed of my forth mortal revelation that there was a non-linear alternative to the birth/life/death story. I remember not being able to determine if it was boring.

But once the movie is recontextualized from a church basement in Princeton, New Jersey and understood at a global level it becomes much more interesting. Reincarnation is, essentially, a global equalizer—it equates all of us by the basis of the value of soul, stripped of the social inequity of body value. Reincarnation is generally anthroposophical, based on the principle that life is for learning, that learning gets us closer to gods/a God and that it takes most of us more than one life to get there. Whether or not one relates to the tenets of reincarnation one can certainly relate to its ideas and apply them to contemporary life and our shared (political, Jungian) histories. An environmentalist would say that each of us leaves a footprint, an ecologist that we each displace energy, a biologist that we are genetically programmed, a sociologist that we are raised by the people around us—in all of these models we inherit and we leave behind.

There was a time when I was 21, just before my grandmother died, that I went to my grandmother’s house for Thanksgiving and we both recognized that she had shrunk and I had grown and that her old clothes fit me perfectly. We were in her room and sitting on her twin size bed in front of the closet as she prepared to get rid of things. It’s strange now to think of this memory and realize that there are people in the worlds who are wearing my grandmother’s old clothing who are not my grandmother, that I could walk by her navy jacket with tacky gold buttons or tweed high-waisted pants and not recognize her. My fifth revelation was my entrance into a global understanding of inheritance.

Collective consciousness is essentially a globalization of experience. I think this is important because it holds us accountable for all life experiences occurring in and before our lifetimes. In the case of Weiss’ patient Catherine the trauma sustained in her own life was impossible to resolve and offered no alleviation from her day-to-day trauma. Whether or not her vocalization of past lives is rooted in true experiences of reincarnation the process seemed to have resolved her symptoms—Weiss reports that after a relatively short period of time she was experiencing a much more positive quality of life having overcome her anxieties, fear of death, reoccurring nightmares and depression without the aid of medication. Weiss muses “…Even if these remarkably explicit visualizations were fantasies, and I was unsure of this, what she believed of thought could still underlie her symptoms. After all, I had seen people traumatized by their dreams. Some could not remember whether a childhood trauma actually happened or occurred in a dream, yet the memory of that trauma still haunted their adult lives (42).”

There have been times that my memory has altered the course of the way I tell stories—in fact, many of the stories I tell about family memories are completely different from the ways other members of my family would tell them, simultaneous and different experiences of the same event. My mother denies any memory of me being forced to sleep alone in my uncle’s bedroom when I was 6—my father swears that he would never have considered letting us watch television in church. Nearing the conclusion of his book Weiss writes, “I wondered how many of our childhood “myths” were actually rooted in a dimly remembered past (161).”

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

things learned, things discerned

Learned a bunch of new words and how to use them properly by reading this silly book by Brian Weiss about past life regression. I also printed out some wild maps charting human consiousness from the internet that I'd like to use in some drawings or collages.

Learned a bunch of new words and how to use them properly by reading this silly book by Brian Weiss about past life regression. I also printed out some wild maps charting human consiousness from the internet that I'd like to use in some drawings or collages.Subconscious- psychic activity below the level of awareness

unconscious- lacking awareness and sensory perception

superconscious- psychic awareness above human awareness

Athazagoraphobia- fear of being forgotten

Xenoglossy- having comprehension of a language with no previous exposure or tutelage

Psychotic- out of touch with reality

Hallucinations- seeing or hearing things not actually there

Delusions- false beliefs

Reincarnation stories were edited from the New Testament by the Romans around 300 AD in response to the concern that they were inconsistent and distracting.

Reincarnation and the in-between planes are basic tenets of kabbalah, Jewish mystical writings that are centuries old.

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

forget me not

Read a fantastic book by Geoffrey Batchen yesterday called Forget Me Not, and here are some of my favorite parts below. The photograph is is a large-format negative in my collection, one side is of the object lit from the front, the other lit from the back.

Read a fantastic book by Geoffrey Batchen yesterday called Forget Me Not, and here are some of my favorite parts below. The photograph is is a large-format negative in my collection, one side is of the object lit from the front, the other lit from the back.In this practice, the photograph is treated as a tangible metaphor, as something one looks at rather then through, as an opaque icon whose significance rests on a ritual rather than on visual truth. While the photograph usually speaks to us of the past, of the time when the photograph was taken, the fotoescultura occupies an ongoing present. While the photograph speaks of death, of time's passing, the fotoescultura speaks of eternal life, suggesting the possibility of a perpetual stasis, the fully dimensioned presence of the present (64).

As a footprint is to a foot, so a photograph is to its referent. Photographs are, scholars have suggested, "physical traces of their objects, " "somethings directly stenciled off the real," even "a kind of deposit of the real itself."

Barthes makes much of the physicality of photography's connection to its subject. "The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here... a sort of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze." (74)

The photograph in my locket was presumably thought to lack something that the addition of hair supplied; but it would appear that the hair alone was also deemed to be not enough-- apparently, neither was fully effective as an act of representation without the presence of the other. Like a photograph, the hair sample recalls the body of the absent subject, turning the locket into a modern fetish object; as a mode of representation, it "allow[s] me to believe that what is missing is present all the same, even though I know it is not the case." (75-76)

Both Plato and Freud use the image of a tablet of wax to describe the operations of memory. In their descriptions, the pristine surface of a wax tablet must be ruined, marked by impressions of "perceptions and thoughts," in order to function as a memory apparatus. The tablet can never actually have been pristine, of course-- for how could we remember something unless some trace were already there, unless the wax had already been shaped or marked in a moment now being recalled?... For memory is always in a state of ruin; to remember something is already to have ruined it, to have displaced it from its moment of origin. Memory is caught in a conundrum-- the passing of time that makes memory possible and necessary is also what makes memory fade and die. (77-78)

Something must be done to the photograph to pull it (and us) out of the past and into the present. (94)

Photography is usually about making things visible, but these elaborated photographs are equally dedicated to the evocation of the invible-- relationships, emotions, memories. They affirm the close proximity of life and death, and attempt, against common sense, to use one to deny the finality of the other. (96)

Memory, to borrow the words of Roland Barthes, is posited here as both artifice and reality, something perceived, invented, and projected, all at once: "whether or not it is triggered, it is an addition: it is what I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there." (97)

One's sense of self, of identity, is buttressed by such objects...In the case of hybrid photographies, for example, individual identity is posited not as fixed and autonomous but as dynamic and collective, as a continual process of becoming. Perhaps this is why these artifacts offer such a powerful experience. Complex object-forms devoted to the cult of remembrance, these photographies ask us to surrender something of ourselves, if they are to function satisfactorily. They demand the projection onto their constituent stuff of our own bodies, but also of our personal recolections, hopes, and fears-- fears of the passing of time, of death, of being remembered only as history, and, most disturbing, of not being remembered as all. (97-98)

Monday, December 7, 2009

migrating

Found this very-used pillow in Portland and brought it back to my studio in San Francisco for contemplation. I love how the geese in the pattern look like they're flying through these dried rings of ancient drool puddles-- so atmospheric! I intend to have a flock of small paper geese migrating off of the surface of the pillow.

Found this very-used pillow in Portland and brought it back to my studio in San Francisco for contemplation. I love how the geese in the pattern look like they're flying through these dried rings of ancient drool puddles-- so atmospheric! I intend to have a flock of small paper geese migrating off of the surface of the pillow.

Saturday, December 5, 2009

louis porter's stains

Photographs of Louis Porter for a project finding and capturing stains in hotels. I wish I made them first! I've only been recently focusing on stains as opposed to wear of objects that I'm drawing.. interesting to go from working with negative to positive processes with the same objects and set of concerns. I suppose the greatest difference is that a hole is evidence of momentary or sustained trauma subjected upon a piece of fabric, the breakdown of an object-- whereas stains are more bodily and applied.

Photographs of Louis Porter for a project finding and capturing stains in hotels. I wish I made them first! I've only been recently focusing on stains as opposed to wear of objects that I'm drawing.. interesting to go from working with negative to positive processes with the same objects and set of concerns. I suppose the greatest difference is that a hole is evidence of momentary or sustained trauma subjected upon a piece of fabric, the breakdown of an object-- whereas stains are more bodily and applied.

Friday, December 4, 2009

how to discern the truth

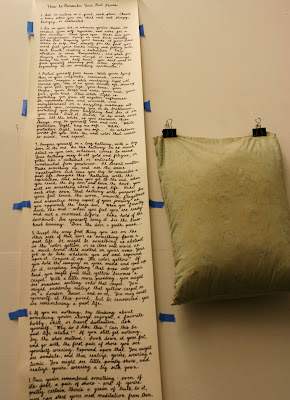

After weeks of intention I finally made time to hand-scribe the directions for How to Remember Your Past Lives. I'm reading a book titled Many Lives, Many Masters which chronicles a psychologist's professional experience with treating a patient who regressed to previous lives through hypnosis, written by Brian L. Weiss, M.D.. The book was suggested to me by several past-life regression therapists over the phone but it wasn't until it came up in conversation with visiting artist Stephanie Diamond during a studio visit back in October that I finally bit the bullet and got a used copy.

After weeks of intention I finally made time to hand-scribe the directions for How to Remember Your Past Lives. I'm reading a book titled Many Lives, Many Masters which chronicles a psychologist's professional experience with treating a patient who regressed to previous lives through hypnosis, written by Brian L. Weiss, M.D.. The book was suggested to me by several past-life regression therapists over the phone but it wasn't until it came up in conversation with visiting artist Stephanie Diamond during a studio visit back in October that I finally bit the bullet and got a used copy.The book is strange-- I go back and forth between believing it and being completely non-plussed. The format of the book is narrative from the first-person of the author/psychotherapist as he linearly reveal a case study of one of his patients and their shared experience of learning about her past lives during their sessions. The story is told with a lot of conviction and having watched videos online of this guys telling his story I've got to admit that there is not a bone in my body that doesn't WANT to believe. But then silly things will happen... like the patients regression to a life in 1483 where she talks about eating corn in Europe-- and that, my friends, is just historically implausible. It's interesting of course because I'm holding this woman responsible for the truth of her memories of past lives hundreds of years ago while I simultaneously forgive the fallacy of my own memory. I have just few more chapters to go and am excited to see where the last page leaves me.

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

still thinking

I talked to James Gobel on Monday about my reluctance to simplify the meaning of my images by talking about them as holes or windows. A few weeks ago Jeff Gibson said I was dumbing down my work by talking about it in terms of 'absence' and 'presence'-- I didn't believe Jeff at first but then I started seeing a bunch of first-year MFA students with pieced titled things like "Absence" and I panicked because I realized HE WAS SO RIGHT. So now I'm on a mission to not use dumb-words. Anyways, James was quiet for a second before having one of his epiphanies about how my images were like cartouches. I told him I would look it up in the dictionary and think about it:

I talked to James Gobel on Monday about my reluctance to simplify the meaning of my images by talking about them as holes or windows. A few weeks ago Jeff Gibson said I was dumbing down my work by talking about it in terms of 'absence' and 'presence'-- I didn't believe Jeff at first but then I started seeing a bunch of first-year MFA students with pieced titled things like "Absence" and I panicked because I realized HE WAS SO RIGHT. So now I'm on a mission to not use dumb-words. Anyways, James was quiet for a second before having one of his epiphanies about how my images were like cartouches. I told him I would look it up in the dictionary and think about it:cartouche, noun

1. a gun cartridge with a paper case

2. an ornate or ornamental frame

3. an oval or oblong figure (as on ancient Egyptian monuments) enclosing a sovereign's name

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

jaundiced

So in love with this color today. When Will was born he was yellow like this-- even the red wine stain on his lower back seemed yellow. Looking closely at this picture too it becomes clear that this was, at some point, a color photograph with reds and greens. Now the only bright spot is the bounce of light off that crease in the corner. My day promises to be monotonously colored like this picture judging by the pile of unread books next to me.

So in love with this color today. When Will was born he was yellow like this-- even the red wine stain on his lower back seemed yellow. Looking closely at this picture too it becomes clear that this was, at some point, a color photograph with reds and greens. Now the only bright spot is the bounce of light off that crease in the corner. My day promises to be monotonously colored like this picture judging by the pile of unread books next to me.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)